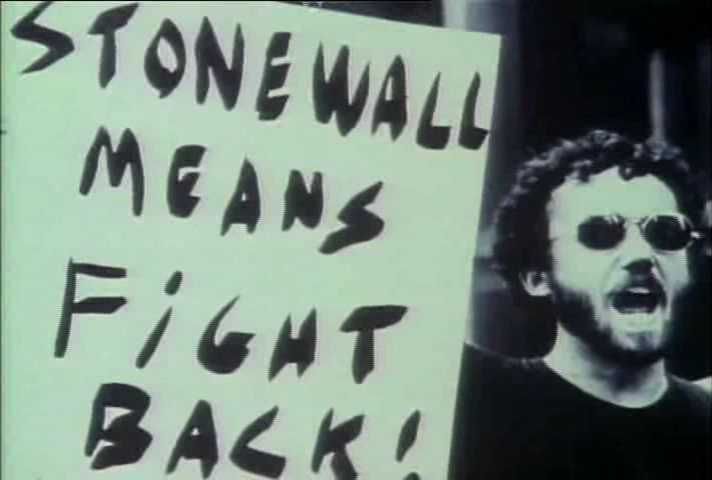

Nearly everyone with even a rudimentary knowledge of the homosexual experience in America is familiar with Stonewall, not just as a NYC dive-bar, but also as the flashpoint in the struggle for Gay Rights. But the “riots”, as they’ve come to be called, didn’t so much spontaneously combust as explode after the participant’s suffering had reached the end of a long simmering fuse.

Post-World-War-2 America was gripped with fear. The reaction was in sharp contrast to that felt after the first world war. Then, waves of isolationism soothed the country’s lingering regrets about mixing in what many considered “European Affairs” (where that left Japan, China, Australia and the Middle East, one can only wonder, though the as yet lingering colonialist condescension toward Africa explains why not much is ever made of their involvement). WW2, on the other hand, saw America fostering her own imperial ambitions, not least in the schismed states that were the former Germany, but also, and at a greater ultimate price, in Southeast Asia.

The main boogey man was of course the Communist. This was partly a reaction to New Deal socialism, but also the Soviet Union had proved in the war a world power to be reckoned with. A secondary threat were homosexuals. The two were linked (almost inexorably so) not so much rationally, but as a result of their insidiousness and their perceived threat to the American way of life.

Yet, concerning the so-called Commie and Pervert Purges, John Loughery writes in The Other Side of Silence: Men’s Lives & Gay Identities – A Twentieth-Century History:

| “[T]wo facts do stand out that never seem to find their way into histories of the Cold War or books about America in the 1950s. …[T]he number of men and women dismissed for sexual reasons far exceeds—by any estimates—the number dismissed for real or alleged involvement with the Communist Party…[And] for the first time, the federal government had addressed itself to the place of the homosexual in American society and concurred with those who argued that gay men and lesbians were not like other people and should not be trusted.” |

The focus on the homosexual over the Communist grew as firebrand senators such as Joe McCarthy lost relevance, and prevailed well into the late sixties.

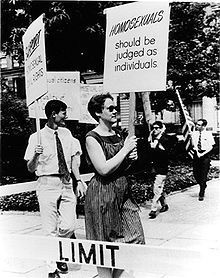

It was amidst this aura of repression and fear that various homophile groups joined together for the Annual Reminder. (While the modern usage of the word gay has arguably been around since the turn of the last century, in the fifties and sixties, to be “pro-gay-rights” was usually known as being “homophile”.) The brain child of activist Craig Rodwell, following smaller pickets outside New York’s Whitehall and the United Nations Plaza, the picket’s title referenced the fact the public needed to be reminded that not all US citizens enjoyed equal rights. Under the auspices of the East Coast Homophile Organizations (ECHO), the event brought together gay rights champions from all across the spectrum. Frank Kameny, a former Army astronomer dismissed due to his homosexuality, is remembered today for legally challenging his dismissal, perhaps the first to do so. Clark Polak founded Drum magazine. Barbara Gittings, a founder of the NY chapter of the Daughters of Bilitis (which official disavowed the picket), also edited DOB’s publication, The Ladder. Kay Tobin Lahusen is recognized as the first openly gay American woman photojournalist. And Rodwell himself went on to establish the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop.

|

Barbara Gittings on the picket line in 1966. |

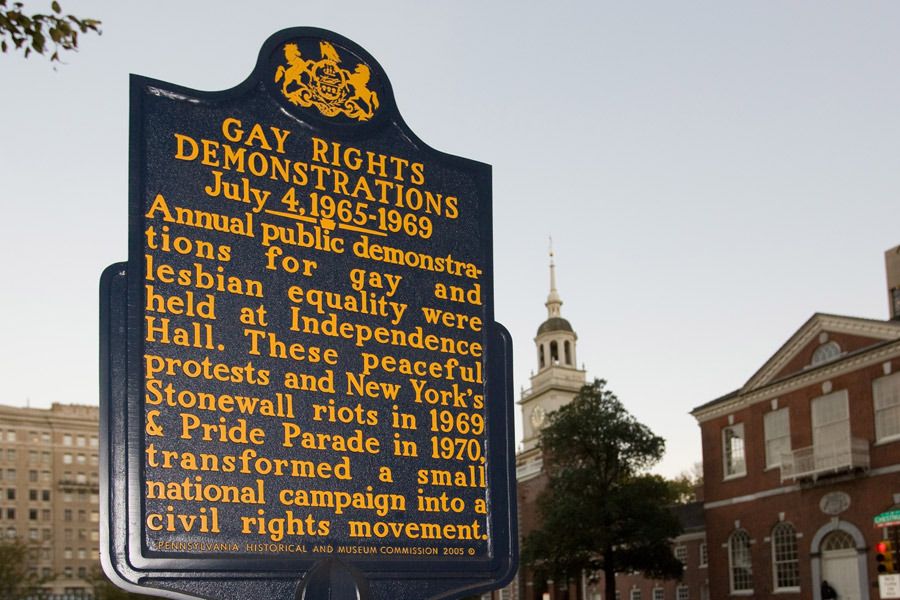

The Annual Reminder focused on ending the legal exclusion of homosexuals in the workplace (especially in government jobs), but lasted only five years. In June of 1969 just a week before the final Annual Reminder, the police infamously raided that dive-bar I mentioned. Subsequent to those events, the pickets were considered almost quaint.

Modern hindsight also tends to underestimate the value of the pickets. They are often derided as arguments for assimilation over acceptance or identity. For example, the 1995 semi-musical film Stonewall all but dismisses the pickets as ineffectual. But even as someone who’s early manhood was steeped in the in-your-face civil disobedience of Act-Up, I can’t help but admire these brave men and women, who really risked far more than I ever did.

In 2005, the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission commemorated the Annual Reminders

with a state historical marker at 6th and Chestnut Streets. On July 4, 2015, to celebrate the picket’s 50th anniversary, a recreation of the first Annual Reminder was staged.

|

Jon Wilson is the author of Cheap as Beasts, a current finalist for the Lambda Literary Award Best Gay Mystery of 2015. He’s also written a follow-up volume, Every Unworthy Thing, as well as two westerns. He lives and works in Northern California. |

May 23, 2016 at 11:32 am

Thanks for posting. This hop is very ejicashunal!

May 23, 2016 at 12:05 pm

I suspect you’re teasing me, but I’ll take it at face value and say pleasure’s all mine. ;P

May 23, 2016 at 2:02 pm

For once I’m not teasing. I knew very little about this.

May 23, 2016 at 3:20 pm

If never heard of the Annual Reminders. Thanks, Jon. This is really interesting.

May 23, 2016 at 10:55 pm

I first learned of it in the Stonewall movie (where, like I mentioned, they sort of make fun of it). It seems remarkable brave to me now that I know more about the period.

Thanks for reading.

May 24, 2016 at 2:25 pm

Hi Jon – I love our history, and it’s been years since I voraciously read Jonathan Ned Katz’s Gay American History, Daniel Greenberg’s The Construction of Homosexuality, etc. as a young, budding activist. So I really appreciated your article for IDAHOT, especially your point about picketers that I hadn’t thought about before. Both Stonewall films use the political organizations of the day as a foil to the “real” agents of change (the hustlers, drag queens and lesbians who started the rioting), and I agree that’s a disservice. A point could be made that those early organizations were not a welcoming umbrella for LGBTs of color, the poor, and Ts at all. Though there’s a context to be understood, and I agree that early homophile organizations deserve some credit for moving the LGBT rights movement forward.

May 25, 2016 at 12:42 am

Yes, regrettably much of the early homophile movement was indeed very geared toward acceptance and assimilation by/with the dominate culture, which did not lend itself to being open to a diversity of influences. But I think what is often overlooked (by our “modern” eyes) is that those who were most marginalized by necessity had carved out a realm of existence which may (I hate to assume I know something when I can only speculate) have given them community and protection. That was the point I was making with ‘these people risked far more than I ever did’. And of course there’s no denying the riots and in-your-face actions that finally occurred were a giant leap forward (or forwardish anyway).

As Inspector Kemp says: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=buvSIrFi0Hw