Search Results for 'ireland'

Did you find what you wanted ?

January 28, 2011

Sculpture in Ardee, County Lough, of Cuchullain carrying Ferdia's body.

Celtic culture was ever a warrior culture, no matter where and when they resided, and as such were part of the virtually global tradition of warrior lovers.

Celtic language, culture and traditions once spanned most of the continent of Europe, bringing it into contact with the classical societies of Greece and Rome for hundreds of years. Celts at their widest expansion, that is, by 275 BC, ranged from the Ukraine west to Spain, France and, of course, the British Isles. Rome sought to incorporate these peoples as they conquered their lands, but Germanic migration forced the contraction of Celtic language and cultures until they occupied only parts of the British Isles and Brittany.

Celts themselves relied entirely on oral tradition for perpetuating their way of life; so Classical scholars and military leaders recorded much of what we know about these peoples. It is remarkable that coming from a culture that recognized and honored same sex relationships, the Greek teacher Aristotle comments in his Politics (II 1269b) on the greater enshrinement of warrior lovers among the Celts. Coincidental with this was a sometimes-disputed tradition of warlike women, or at least greater liberty for women in and out of matrimony. Brehon law, which governed Irish tribes, for example, permitted divorce initiated by wives.

In ancient Irish mythology, male warriors paired off much as the great male lovers of ancient Greece, such as Achilles and Patroclus and Alexander and Hephaestion. They shared a bed and fought as a team. Perhaps best known of these couples is Cuchullain and Ferdia. Cuchullain was semi-divine, almost invincible and able to turn into a ravening beast in battle. In the legend, the two lovers are forced to meet in battle to the death. At the end of each day of hand to hand combat, they met in the middle of a ford to embrace and kiss three times. When Cuchullain finally kills his friend, he mourns, singing over his body,

Dear to me thy noble blush,

Dear thy comely, perfect form;

Dear thine eye, blue-grey and clear,

Dear thy wisdom and thy speech.

(Quoted in “A Coming Out Ritua“l)

Even after the Christianization of Ireland the record in regards to acceptance of same sex relationships is ambiguous. According to Brian Lacey’s new history of homosexuality in Ireland, Terrible Queer Creatures: A History of Homosexuality in Ireland, St. Patrick traveled with a lifelong companion his that he is recorded as having great affection for and sleeping with. In the famous illuminated gospel, The Book of Kells, there are numerous illustrations of men embracing. In typical Christian revisionist manner, the Church has interpreted these illustrations as calling for the eradication of sodomy.

One person in a chieftain’s household, the poet/bard called the ollamh was afforded great access to his lord physically, sharing his bed and demonstrating affection with him in public. In songs or poems the ollamh often referred to the chieftain as a beloved or even a spouse. It is interesting in Dorothy Dunnett’s sexually ambiguous Lymond Chronicles the protagonist in the second volume, Queen’s Play, masquerades not as any other sort of bard but as an ollamh. The tradition continued well into the Middle Ages.

Ireland’s homophobia is now being confronted in its courts where it is likely the prohibition against same sex marriage will go the way of the ban on contraception.

November 3, 2016

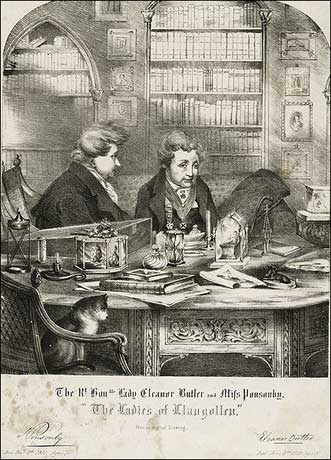

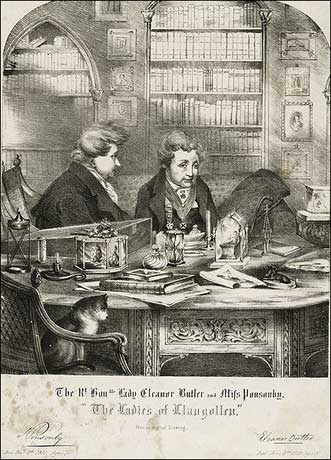

Extraordinary Female Affection was the title of a 1790 newspaper article on two female friends, Miss Sarah Ponsonby and Lady Eleanor Butler, who had defied convention by running away to live together.

Extraordinary Female Affection was the title of a 1790 newspaper article on two female friends, Miss Sarah Ponsonby and Lady Eleanor Butler, who had defied convention by running away to live together.

The article, which appeared in St. James’s Chronicle, the General Evening Post and the London Chronicle, made it quite plain what the author thought of such goings-on, describing Butler in disapproving tones as of masculine appearance (this was true) and the couple as bear[ing] a strange antipathy to the male sex, whom they take every opportunity of avoiding – which was decidedly false; the ladies entertained many male guests, including the Duke of Wellington, Sir Walter Scott and William Wordsworth. The author described Ponsonby as Butler’s particular friend and, more censoriously (for the time), the bar to all matrimonial union. Needless to say, the ladies were less than happy with the tone of the article, and took legal advice.

However, the attitude of society in general was very different. The zeitgeist of the time was for romanticising all things, including nature, landscapes and the bonds of friendship, and their story captured the popular (educated) imagination. The ladies were celebrated for their romantic friendship and presumed celibacy, to the extent that they became celebrities of the day—similarly, one supposes, to many early female Christian martyrs who were lauded for their chastity as much as for any miraculous deeds.

There is plenty of the romantic in the ladies’ story: both were from aristocratic (though attainted) families in Ireland and both were under intolerable pressure from their families—Butler to enter a convent, and Ponsonby to accept the advances of her guardian. Close friends for many years, when Ponsonby was 23 and Butler, 39, they hatched a plot to run away together dressed as men, taking with them a pet dog and a pistol. Having ridden through the night to catch a ferry to Wales, they were hit by what we tend to think of as a bane of modern life: transport cancellation. Unluckily, they were discovered and brought back home.

Much as for Marianne in Sense and Sensibility by Jane Austen (who would have known of the Ladies of Llangollen), for Ponsonby, romantic disappointment was swiftly followed by dangerous illness. To comfort her friend—and escape her family, who had stepped up attempts to ship her off to that convent—Butler fled to Ponsonby’s house, where she concealed herself in her friend’s bedroom, aided by a sympathetic maid, Mary Carryl. When, after some days, she was discovered, the families evidently decided that enough was enough, threw up their hands and consented to the couple removing to Wales as they’d wanted all along.

Ponsonby later wrote up the tale in Account of a Journey in Wales perform’d in May 1778 by Two Fugitive Ladies, showing she had an eye for a catchy, if long-winded, title.

The ladies eventually found a house near Llangollen where they settled down and lived happily for the next fifty years in quiet retirement—apart from the steady stream of society visitors.

Were they lovers? Nobody knows. Even in their own lifetimes, opinion was divided. They addressed each other in terms used between husband and wife, and they shared a bed—but this was not unusual behaviour for friends at the time. They also cropped their hair and wore masculine hats and coats—although retaining their petticoats. Their visitors included Anne Lister, who was, by her own writings, what we would nowadays term a lesbian and had physical affairs with women, and Anna Seward, who although romantically interested in women is not known to have had a sexual relationship with any.

It’s often speculated that Butler, the more obviously masculine of the two, was a lesbian, but that Ponsonby, the younger, more femme partner, might have been just as happy with a man. I personally tend to take this more as evidence for the enduring quality of stereotypes than as anything else.

Further reading: Rictor Norton (Ed.), “Extraordinary Female Affection, 1790”, Homosexuality in Eighteenth-Century England: A Sourcebook, 22 April 2005, updated 15 June 2005 <http://rictornorton.co.uk/eighteen/1790extr.htm>.

Nancy Meyer, Regency Researcher http://www.regencyresearcher.com/pages/ladies.html

***

JL Merrow is that rare beast, an English person who refuses to drink tea. She read Natural Sciences at Cambridge, where she learned many things, chief amongst which was that she never wanted to see the inside of a lab ever again. Her one regret is that she never mastered the ability of punting one-handed whilst holding a glass of champagne.

JL Merrow is that rare beast, an English person who refuses to drink tea. She read Natural Sciences at Cambridge, where she learned many things, chief amongst which was that she never wanted to see the inside of a lab ever again. Her one regret is that she never mastered the ability of punting one-handed whilst holding a glass of champagne.

JL Merrow is a member of the Romantic Novelists’ Association, International Thriller Writers, Verulam Writers’ Circle and the UK GLBTQ Fiction Meet organising team.

Find JL Merrow online at: www.jlmerrow.com, on Twitter as @jlmerrow, and on Facebook at http://www.facebook.com/jl.merrow

JL Merrow is the author of “A Particular Friend” which appears in A Certain Persuasion, a new anthology of stories set in and around the writings of Jane Austen, featuring LGBTQIA characters, which was released on 1st November.

JL Merrow is the author of “A Particular Friend” which appears in A Certain Persuasion, a new anthology of stories set in and around the writings of Jane Austen, featuring LGBTQIA characters, which was released on 1st November.

Thirteen stories from eleven authors, exploring the world of Jane Austen and celebrating her influence on ours.

Being cousins-by-marriage doesn’t deter William Elliot from pursuing Richard Musgrove in Lyme; nor does it prevent Elinor Dashwood falling in love with Ada Ferrars. Surprises are in store for Emma Woodhouse while visiting Harriet Smith; for William Price mentoring a seaman on board the Thrush; and for Adam Otelian befriending his children’s governess, Miss Hay. Margaret Dashwood seeks an alternative to the happy marriages chosen by her sisters; and Susan Price ponders just such a possibility with Mrs Lynd. One Fitzwilliam Darcy is plagued by constant reports of convictions for ‘unnatural’ crimes; while another must work out how to secure the Pemberley inheritance for her family.

Meanwhile, a modern-day Darcy meets the enigmatic Lint on the edge of Pemberley Cliff; while another struggles to live up to wearing Colin Firth’s breeches on a celebrity dance show. Cooper is confronted by his lost love at a book club meeting in Melbourne while reading Persuasion; and Ashley finds more than he’d bargained for at the Jane Austen museum in Bath.

Smashwords| Amazon | ARe

March 10, 2013

This is Tom’s mother from Promises Made Under Fire. Very different kettle of fish from Mrs. S.

Mother met me at the station, full of smiles and news. Father’s back playing up, her head much better, thank you, scandal about the neighbour’s son, who’d somehow mysteriously moved to Ireland.

“And your friend Ben—he asked me to apologise for his not being here to meet you but the silly boy’s gone and got mumps.” She slipped her arm in mine. “So he’s strictly persona non grata.”

She didn’t need to add why—any of my platoon could have told you the risk to a man’s wedding tackle. What the hell had I done to get such a run of luck?

“Have you any plans? Apart from rattling around at home?” Mother squeezed my arm, her hand seeming so tiny against my uniform coat. I patted it.

“I’ve a commission to fulfil. No, don’t worry.” I patted her hand again. “It’s not the army. You remember Foden?”

Of course she did, the way she paled at the mention of the name and gripped my arm tighter. She’d have remembered my tears, too. I hailed a cab and carried on. “He left a letter asking me to make some visits on his behalf. Least I can do.”

“You always were a good lad,” Mother said as we bundled into the cab and gave the driver our address.

Good lad I might be, but I wasn’t looking forward to doing this particular duty. “He wanted me to visit his mother,” I said, looking out of the window, unseeing. “Do you think I should write to her and make an initial introduction, rather than just turn up on her doorstep?”

“It would depend on her character. If it were to bring her distress rather than comfort, she might prefer one dose of it.”

Only one dose of discomfort for me, too; I’d forgotten how wise Mother was. “I have no idea. She’s a cook, up in London.”

“A cook?” A brief look—surprise tinged with quickly hidden disdain—crossed her face.

“It will have hurt her as much to lose her son as it would the lady of the household.” The anger I felt shocked me.

“I’m sorry. You’re quite right. You’ve always said that bullets don’t make any social distinctions.” She suddenly produced a mischievous smile. “And since the ‘to do’ with the lad next door, even Father says you can’t tell how brave someone is from the school he went to. He’s very proud of you, you know.”

February 5, 2013

Although I’ve done a number of historicals now – enough to say I am a ‘historical novelist’ – I still feel that not all historical eras are equal. People have said to me ‘the Tudors are very popular. I’d like to see you do something set in Tudor times.’ I nod politely, because there’s no predicting where my muse might take me next. But inside, I’m still going ‘ew, the Tudors. They’re all torture and paranoia and witch burnings.’ I can’t really imagine wanting to write in an era where my nation’s best battleship sunk because someone forgot to put the plug in.

This is slightly hypocritical of me, because I like the Anglo-Saxons a lot, and they are not without brutality either. Plus, their technological level is much lower. But they nevertheless seem more civilised to me – a thoughtful, religious, melancholy people with less tendency towards burning women alive. Maybe I’m reading too much from the example of King Alfred and the Venerable Bede – both the sort of humane intellects I wouldn’t mind meeting in real life.

The 18th Century, though, is still my favourite. Part of this is the clothes. I can’t take Henry VIII seriously in his padded bloomers, but when we’ve moved on to tricorn hats, poet shirts, tight waistcoats and frock coats with swirling skirts; tight breeches and men in white silk stockings, showing off their toned calves to the ladies, well, then you’re talking.

But it’s more than that. I prefer civilization to savagery – I like to write in a world in which I would not find it unbearable to live – and the 18th Century is a time in which it’s possible to exist as something other than a warrior. More than that, it’s a time of great exploration. The world was opening up before Western Man, and as a result the spirit of the age is one of excitement. New things are being thought of every day. New places are being discovered. The world and the human spirit is expanding, and for the first time people are beginning to think about freedom and equality and the rights of man. An awful lot of what we take for granted nowadays was first being thought of in the 18th Century and it’s fascinating to watch it blowing their minds.

I read a lot of 18th Century journals as part of my research, and I find no difficulty in liking these people. They are urbane and amused, confident and surprisingly open minded. They have none of the self-righteous imperialism and prudery of the 19th Century, and while you’d have to cover the ears of the sensitive, because of their vulgarity, I wouldn’t feel a qualm about inviting them around for dinner. The tendency to fight a duel at the drop of a hat would be worrisome, I suppose, and they do drink and quarrel a lot, but they’re never quite what you expect. I think Jane Austen, who was that little bit later, would be shockingly disapproving of them. But in a fight between Lady Mary Wortley-Montague, lady of letters, who travelled the world, wrote letters from Turkey, and invented an early form of smallpox inocculation, and Jane Austen, my bets are on Lady Mary. She, at least, had attended the Empress of Austria when the fine ladies of Austria exhibited their honed pistol marksmanship. I think she’d be the one to walk away from that duel.

Blurb:

For Captain Harry Thompson, the command of the prison transport ship HMS Banshee is his opportunity to prove his worth, working-class origins be damned. But his criminal attraction to his upper-crust First Lieutenant, Garnet Littleton, threatens to overturn all he’s ever worked for.

Lust quickly proves to be the least of his problems, however. The deadly combination of typhus, rioting convicts, and a monstrous storm destroys his prospects . . . and shipwrecks him and Garnet on their own private island. After months of solitary paradise, the journey back to civilization—surviving mutineers, exposure, and desertion—is the ultimate test of their feelings for each other.

These two very different men each record their story for an unfathomable future in which the tale of their love—a love punishable by death in their own time—can finally be told. Today, dear reader, it is at last safe for you to hear it all.

You can read an excerpt and buy Blessed Isle here at Riptide.

Author Bio

Alex Beecroft was born in Northern Ireland during the Troubles and grew up in the wild countryside of the English Peak District. She studied English and Philosophy before accepting employment with the Crown Court where she worked for a number of years. Now a stay-at-home mum and full time author, Alex lives with her husband and two daughters in a little village near Cambridge and tries to avoid being mistaken for a tourist.

Alex is only intermittently present in the real world. She has lead a Saxon shield wall into battle, toiled as a Georgian kitchen maid, and recently taken up an 800 year old form of English folk dance, but she still hasn’t learned to operate a mobile phone.

You can find Alex on

her website,Facebook,Twitter or her Goodreads page

August 2, 2010

Charles Dance stars as Jack Wolfenden in this drama by Julian Mitchell which tells the human story behind the so-called Wolfenden report.

Fifty years ago, a Home Office committee chaired by Wolfenden, then vice-chancellor of Reading University, recommended the decriminalization of homosexuality. But behind the scenes of what was to become a turning point in British social history, there was an even more extraordinary story. Jack’s son Jeremy, then a brilliant undergraduate at Oxford, was himself gay, something his father could not bring himself to acknowledge.

From the corridors of power in Whitehall to the squalid public toilets of a Reading park, this is a story of fathers and sons, ambition and prejudice, gentlemen and players. Also starring Sean Biggerstaff, Samantha Bond, Haydn Gwynne and Mel Smith.

http://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/b007y9gx/Consenting_Adults/ (sadly only available to the UK, but well worth seeking out on DVD.)

Consenting Adults is a BBC Production which was made in 2007, and for some reason I’ve completely missed until yesterday. Just over an hour long, it’s an absolute must for anyone who has any interest at all in gay history.

It’s a simple enough story–pretty much based entirely on true facts–which relates the reasons for the instigation of the famous “Wolfenden Report” (more correctly known as “Report of the Departmental Committee on Homosexual Offences and Prostitution (1957”)

You’d think that a story of a dry committee, sitting for months and discussing this subject would be incredibly dry as televisual matter, but it couldn’t be further from the truth. As often happens, truth is stranger than fiction and the work done on the report is brought into sharp focus as we discover that Jeremy Wolfenden, the son of John Wolfenden who headed up the report, is homosexual. The relationship between father and son is hugely typical of that time and place – the young man much more confident and striding (or at least on the outside) and desperate for father’s approval and attention–and neither man able even to touch each other in friendship. Wolfenden senior tells Jeremy that he’d better stay away from home while the enquiry is on.

I learned something too–like many many people I’d been pronouncing it homo (as in go go) when it should be pronounced homo (to rhyme with dom-oh) because it’s from the greek which means “same” and not the latin which means “man.” Coo, the things you learn off the telly, eh?

The Report had been commissioned to see if any changes in the law were required, not only in homosexual cases, but in the matter of prostitution, as street prostitution was increasing, causing more people to be arrested, which hit the newspapers, creating moral outrage. With homosexuality, more and more men were being arrested for sodomy, attempted sodomy, public indecency and other acts under the Offences Against the Person Act 1861 –which had not been altered since the infamous Labouchere Amendment of 1885–making every homosexual act illegal, in private or no. The Labouchere Amendment had created “A Blackmailers Charter” and because men were turning each other in through fear, or, when they were arrested themselves, their phone books were finding many other men of the same inclination.

It seemed to the public at large that homosexuality was increasing in huge leaps and bounds, whereas it was simply the law, and enthusiastic police regimes which were causing the perceived growth. More and more public figures were thrown into the spotlight, having been arrested for “public indecency.” Oscar Wilde was famously the first, but many others followed, and in the fifties, famous cases were splattered all over the headlines.

Sir John Gielgud

In 1953, Sir John Gielgud, was arrested after trying to pick up a man in a public toilet who turned out to be an undercover policeman. He was found guilty of “persistently importuning for immoral purposes.

In 1954, Lord Montagu of Beaulieu, then a 28-year-old socialite and the youngest peer in the House of Lords, was jailed for a year, on a charge he has always denied. He was convicted along with the Daily Mail journalist Peter Wildeblood and the Dorset landowner Michael Pitt-Rivers in a sensational case that made headlines around the world. It is thought today that these three arrests, following on from Geilgud’s cottaging scandal,

Peter Wildeblood

brought about the instigation of the Report.

(For additional viewing, the tale of Peter Wildeblood and Lord Montagu’s trial is told in a 2007 Channel 4 drama-documentary, A Very British Sex Scandal.)

What I found fascinating was the people who were elected to be on the Report’s Committee. Certainly at first glance, these people seem to be the very worst of those that could have been chosen. MPs, the leader of the Girl Guides, Church leaders, psychiatrists and doctors. If you’d asked me to bet (were I to live in that time) I would certainly have said that the law would have been strengthened, not lessened, but perhaps it goes to show that even I shouldn’t take things on face value.

This committee, despite most of them being revolted by homosexuality, voted almost unanimously (James Adair, former Procurator-Fiscal for Glasgow being the only objectee) to change the law in England and Wales, that as long as homosexual behaviour was behind closed doors, between Consenting Adults (over 21 at the time, although the age of consent was eventually lowered to today’s 16) then it should not be an offence. The law did not take into account the Merchant Navy or the Armed Forces, an oversight that has caused much grief, and one that was only righted very recently.

Sadly, and Laird’s reaction was an omen of this, Scotland and Northern Ireland did not take the crime of homosexuality off their statute books until 1980 and 1982 respectively. And it has to be said – even England did not race to take on board the recommendations of the Report, and it took a good ten years for the recommendations in the Report to become law with the new Sexual Offences Act 1967.

Wolfenden’s son, Jeremy, was a startlingly intelligent young man and was approached for recruitment as a spy by the Secret Intelligence Service whilst he was doing his National Service. It is stated in the film that they knew he was “queer” – and it’s more than probable that they did. He eventually accepted their offer and went to Moscow, but his drinking eventually killed him. He was found dead in his bath at the age of 31. It is suspected that he died of suspicious causes, particularly as was playing a dangerous double game between MI6 and the KGB, that he became friends with Guy Burgess (infamous defector and fellow homosexual) whilst in Russia, and that he had been a victim of attempted blackmail after pictures were taken of him in bed with a Russian man.

What is particuarly poignant about the film is that it does not shy away from the fact that prosecutions continued vigourously up to and after the Report. Sodomy could result in life imprisonment, attempted sodomy in ten years. There are two particular stories in the film which show how sad and desperate men’s lives were in the era. Highly recommended.

July 14, 2010

Or – as some might say, not the Good Word.This post may be offensive to some, so don’t click below the link if a certain C word offends you.

There’s been an interesting discussion on one of the author’s groups I belong to. It’s about a well-oiled subject which is brought up from time to time and that’s the usage of slang/coarse/”insulting” words for genitalia to describe genitalia.

One of the words discussed was the big “C word”. Now, that’s not a word you’ll ever hear me say. I flinch when I hear someone say it, and I don’t know why exactly, conditioning, whatever. I don’t have a problem with many words, although I don’t swear a good deal unless very cross.

Someone asked where the word came from – so I duly popped along to the two bibles I use for etymology, namely etymology online and the Oxford English Dictionary.

Here’s what they said. (more…)

June 23, 2009

by Leslie H. Nicoll

If you want to be a Macaroni, you have to be a stickler for historical accuracy. Not to scare anyone off, but to me, half the fun of writing historical fiction is doing the research. I love looking up things and learning new tidbits of information. Doesn’t everyone?

This is on my mind because I just finished The Help by Kathryn Stockett. While it was a very good book and I enjoyed it very much, there were a couple of historical anachronisms that I picked up on instantly. Imagine my amazement when I got to the Acknowledgments and Postscript and the author actually admitted to them! Worse, she did not give a reason for why they were included and why she did not change them.

This is on my mind because I just finished The Help by Kathryn Stockett. While it was a very good book and I enjoyed it very much, there were a couple of historical anachronisms that I picked up on instantly. Imagine my amazement when I got to the Acknowledgments and Postscript and the author actually admitted to them! Worse, she did not give a reason for why they were included and why she did not change them.

The errors, as she states, were, “Using the song, ‘The Times They Are A-Changin,’ even though it was not released until 1964 and Shake ‘n Bake, which did not hit the shelves until 1965.”

Certainly Bob Dylan is an iconic folk singer, but there were plenty of folkies on the radio waves in 1962 and 1963 (the principal time of the action in the book). If she wanted to stick with Dylan, why not use “Blowin in the Wind,” released in 1963, which certainly addresses issues of freedom and change. Peter, Paul and Mary would be another choice, with hits such as “Lemon Tree” (maybe not too applicable, although the character listening to the music does have a rocky-to-non-existent love life) or “If I Had a Hammer.” My point is, while “The Times They Are A-Changin” is compelling, I don’t think it is compelling enough to rewrite history to include it.

Then there’s the Shake ‘n Bake error. Shake ‘n Bake is mentioned three times in the book, in two different scenes. The first:

Then there’s the Shake ‘n Bake error. Shake ‘n Bake is mentioned three times in the book, in two different scenes. The first:

Miss Celia puts a raw chicken thigh in, bumps the bag around. “Like this? Just like the Shake ‘n Bake commercials on the tee-vee?”

“Yeah,” I say and run my tongue up over my teeth because if that’s not an insult, I don’t know what is. “Just like the Shake ‘n Bake.”

So the maid is teaching her employer to cook and the employer (Miss Celia) is all about shortcuts and making it easy. Fine, but does it have to be Shake ‘n Bake, three years before it was invented? How about a Duncan Hines cake mix or Betty Crocker brownie mix? Or, it the author wants to subtly address issues of race and class (the overarching theme of the book), why not have her suggest Aunt Jemima pancake mix? That would certainly be insulting to the maid, Minny, moreso than Shake ‘n Bake, which didn’t even exist.

The other time Shake ‘n Bake is mentioned in the book is in this line, “Wondering if, for no good reason I started thinking about Sears and Roebuck or Shake ‘n Bake, would it be because some Illinoian had thought it two days ago. It gets my mind off my troubles for about five seconds.” Just draw a blue line through that Shake ‘n Bake. No need to even include it.

As I said at the beginning, I enjoy doing the research for writing a historical story. I just finished a 33,000 word novella (due to be published in six months). The story takes place in the era of World War II and after. Some of the things I learned while researching various facts for the book:

- Western Union delivery methods, in both the city and the country. In the city, they had delivery men who rode bikes. Out in the country, the Western Union operator was responsible for delivering telegrams, usually in the afternoon after receiving the telegrams in the morning.

- Gone With the Wind premiered in December, 1939, but did not go into wide release in the US until 1941. For six months in 1940, it was in shown in “reserved seat, roadshow engagements,” a format for showing movies that was very popular in the 1940s and 1950s, but is non-existent now. (Note: Gone With the Wind doesn’t even show up in the book. The characters go see The Wizard of Oz, instead, which came out in the summer of 1939.)

- In 1942, the Queen Mary was transporting more than 15,000 US servicemen to England, in preparation for the D-Day invasion. Off the coast of Ireland, the Queen Mary collided with—literally sliced through—one of her escort ships, the HMS Curacao. The Curacao quickly sunk and 338 men perished; only 102 of the crew survived. This tragedy was not made public until after the war ended. Even now, it is sort of hushed up. It is not a proud moment in British and US naval history.

- US families who had loved ones killed in Europe in WWII did have the option to have the soldier’s body sent home to the US for final burial, although it was a complicated and time consuming process that could take years.

- Gay bars in New York city in the early 1960s were dingy, dark, dumpy places that served overpriced drinks, didn’t meet basic sanitation codes, and were run by the Mob. There was a crackdown on all sorts of “undesirable activity,” including known homosexual hangouts, in New York in 1962 and 1963, as Mayor Wagner was trying to “clean up the city” for all the visitors who were expected to come to New York to attend the World’s Fair. Reading about gay bars got me off on a tangent about bath houses and I learned a lot about those, too. In the end, my character didn’t even go to a gay bar, he just went to the bar in his hotel. The logistics of getting him from Madison Avenue and 45th Street to Greenwich Village, location of most of the gay bars, was just too convoluted.

HMS Curacao

Those are just a few facts off the top of my head—I could come up with plenty more. My point is, if you are going to step up to the plate to write historical fiction, then you need to accept the fact that part of the writing process will involve research and fact checking. If you skip this important component of the process, you run the risk of making finicky readers—like me—unhappy.

Kathryn Stockett, shame on you.

Leslie H. Nicoll writes fiction under the pen name of E. N. Holland. Her novella, Our One and Only, will be included in the military history anthology, Hidden Conflict: Tales from Lost Voices in Battle, due to be published in January 2010 by Bristlecone Pine Press and Cheyenne Publishing. You can learn more at her Facebook page, http://www.facebook.com/leslie.nicoll or LiveJournal, lazylfarm.livejournal.com.

November 18, 2008

There are lots of modern myths about the past which it’s very easy for us as modern people to buy into. I was thinking about this today because I’ve recently acquired a number of reprints of 18th Century journals, and I keep coming across sentiments which are startlingly at odds with what popular thought believes about 18th Century people.

We’re accustomed to the idea that the past was a different place from the present – that people thought in ways which are at odds with our modern understanding – but I think that our tendency is to make that a value judgement. The people of the past were old fashioned and wrong. They believed things which no progressive modern person would ever believe. They were, in short, not as good as us.

One of the joys of reading original sources, however, is the way that they challenge this assumption. Yes, the past was different from the present, but it was often different in ways we don’t really suspect, and in ways that challenge our casual assumption of modern superiority.

For example, the idea that women in the past were somehow less critical of men; they were passive wallflowers without a thought of their own, in comparison with modern, kickass heroines.

By contrast I just found this opinion in the correspondence of Mary Delany (published as ‘Letters from Georgian Ireland’ edited by Angelique Day)

Dublin 17 January 1731/2

Would it were so, that I went ravaging and slaying all odious men, and that would go near to clear the world of that sort of animal; you know I never had a good opinion of them, and every day my dislike strengthens; some few I will except, but very few, they have so despicable an opinion of women, and treat them by their words and actions so ungenerously and inhumanly. By my manner of inveighing, anybody less acquainted with me than yourself would imagine I had very lately received some very ill usage. No! ’tis my general observation on conversing with them: the minutest indiscretion in a woman (though occasioned by themselves), never fails of being enlarged into a notorious crime; but men are to sin on without limitation or blame; a hard case!

It’s a complaint I hear daily echoed around my Livejournal communities, and so startlingly familiar that I laughed out loud. Who would have thought it – we’ve been complaining about the double standard for over two hundred years. Of course, in the next line she breaks that familiarity by continuing – not the restraint we are under, for that I extremely approve of, but the unreasonable licence tolerated in the men. How amiable, how noble a creature is man when adorned with virtue! But how detestable when loaded with vice!

These days we would rather argue for the right of women to behave with the licence she detests in her men, rather than the duty of men to behave with the self restraint she hopes for in women, but still it’s apparent that our foremothers were not quite as uncritical as they are sometimes supposed to be.

Another myth that doesn’t quite stand up to the evidence of the original sources is the idea that the 18th Century explorers went out with a doctrine of Imperialism and certainty of superiority, intent on dispossessing the peoples they found of their culture and lands.

With hindsight developed from watching the ghastly results of that first contact, we work backwards and assign the original explorers motives and world-views that are quite inaccurate. In doing so – in our haste to make it plain that as modern people we abhor imperialism in any form – we misrepresent the attitudes of the time.

This is Captain Cook exhibiting his feeling of cultural superiority in Tahiti

We refused to except of the Dog as being an animal we had no use for, at which she seem’d a little surprised and told us that it was very good eating and we very soon had an opportunity to find that it was so, for Mr.Banks having bought a basket of fruit in which happened to be the thigh of a Dog ready dress’d, of this several of us taisted and found that it was meat not to be dispised and therefore took Obarea’s dog and had him immidiatly dress’d by some of the Natives in the following manner. (Cook describes cooking in a hole in the ground.) after he had laid here about 4 hours the Oven (for so I must call it) was open’d and the Dog taken out whole and well done, and it was the opinion of every one who taisted of it that they Never eat sweeter meat, we therefore resolved in the future not to despise Dogs flesh.

Cook on the superiority of Christianity to Tahitian religion:

Various were the opinions concerning the Provisions &c laid out about the dead; upon the whole it should seem that these people not only beleive in a Supream being but on a futurue state also, and that this must be meant either as an offering to some Deitie, or for the use of the dead in the other world, but this last is not very probable as there appear’d to be no Priest craft in the thing, for what ever provisions were put there, it appear’d very plain to us that there it remaind untill it consum’d away of it self. It is most likely that we shall see more of this before we leave the Island, but if it is a Religious ceremoney we may not be able to understand it, for the Misteries of most Religions are very dark and not easily understud even by those who profess them.

My emphasis added. Do these sound to you like the opinions of a man certain that he was the spearhead of civilization? I’m not for a moment denying that his arrival in many of the places he visited was the start of a disastrous and appalling period of exploitation and oppression. Nor that the Imperialism and cultural superiority followed, but the myth tends to be that the first explorers arrived with ill intent. When you read the man’s actual thoughts it’s much harder to keep hold of that.

Cook is not what you expect. And he’s not what you expect in a different way from what you might expect, because although many of his entries read with an almost Star Trek ‘strange new worlds’ delight in discovering new things which I for one find easy to empathize with, in many other places he is as archaic and strange as you can imagine. Here’s his entry in the log for a tragedy early in the voyage:

In the morning hove up the Anchor in the Boat and carried it out to the Southward, in heaving the Anchor out of the Boat Mr Weir Masters mate was carried over board by the Buoy-rope and to the bottom with the anchor. Hove up the anchor by the Ship as soon as possible and found his body intangled in the Buoy-rope. Moor’d the ship with the two Bowers in 22 fathom water, the Loo Rock W and the Brazen head E Saild his Majestys ship Rose. The Boats imploy’d carrying the casks ashore for Wine and the caulkers caulking the Ships sides.

As modern people we would expect at least a conventional expression of emotion here, but there is none.

To sum up; the past is strange, but it’s strange in ways that we don’t expect. If it’s possible at all to find original sources there is no substitute for them in correcting the assumptions we take for granted as modern people. In many respects, once we start to hear the genuine voices of people from the past it becomes much clearer that we aren’t superior to them; that we, like them, are subject to our own culture’s prejudices. Original sources – there’s nothing like them for broadening the mind and the sympathies. (And in Cook’s case, also the spelling. I’m going to have such trouble not writing clowdy and intangled in future!)

October 28, 2008

‘I never knew a woman brought to sea in a ship that some mischief did not befall the vessel‘

Admiral Cuthbert Collingwood

That ladette of the Royal Navy (movie “Carry On Jack”)

It usually starts with the question “… and what are you writing about?”

I’ll reply “historical gay romance” to keep it short. Actually, I write historical adventure with supernatural elements and gay romance. However, “romance” is all people hear, and they immediately wrinkle their noses. They think of the novelettes about handsome rich doctors and beautiful poor nurses you can buy at the newsagents. Or of a 800 page novel with a cover showing a half-naked damsel in distress, kneeling in front of Fabio with a torn shirt. To them, romance is icky. It’s not intellectual. It’s written by women wearing fedoras and read by women with no career or too much time at hand. Romance is the equivalent to stepping barefoot on a slug.

Once they learn that my stories are set in the 18th century and the main characters are serving in the Royal Navy, things get pear shaped. Accusations of “supporting imperialism and war crimes” are thrown around. The 18th century, so I’ve been told, can’t be used as background for any romance because it was a brutish age full of injustice, and placing a loving couple right in the middle of it would be far too frivolous.

Darn it, there go Aimée and Jaguar.

(more…)

Extraordinary Female Affection was the title of a 1790 newspaper article on two female friends, Miss Sarah Ponsonby and Lady Eleanor Butler, who had defied convention by running away to live together.

Extraordinary Female Affection was the title of a 1790 newspaper article on two female friends, Miss Sarah Ponsonby and Lady Eleanor Butler, who had defied convention by running away to live together. JL Merrow is that rare beast, an English person who refuses to drink tea. She read Natural Sciences at Cambridge, where she learned many things, chief amongst which was that she never wanted to see the inside of a lab ever again. Her one regret is that she never mastered the ability of punting one-handed whilst holding a glass of champagne.

JL Merrow is that rare beast, an English person who refuses to drink tea. She read Natural Sciences at Cambridge, where she learned many things, chief amongst which was that she never wanted to see the inside of a lab ever again. Her one regret is that she never mastered the ability of punting one-handed whilst holding a glass of champagne. JL Merrow is the author of “A Particular Friend” which appears in A Certain Persuasion, a new anthology of stories set in and around the writings of Jane Austen, featuring LGBTQIA characters, which was released on 1st November.

JL Merrow is the author of “A Particular Friend” which appears in A Certain Persuasion, a new anthology of stories set in and around the writings of Jane Austen, featuring LGBTQIA characters, which was released on 1st November.

Then there’s the Shake ‘n Bake error. Shake ‘n Bake is mentioned three times in the book, in two different scenes. The first:

Then there’s the Shake ‘n Bake error. Shake ‘n Bake is mentioned three times in the book, in two different scenes. The first: