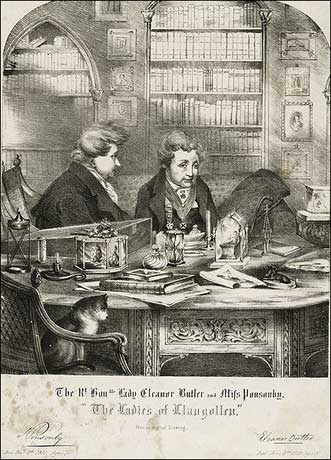

Extraordinary Female Affection was the title of a 1790 newspaper article on two female friends, Miss Sarah Ponsonby and Lady Eleanor Butler, who had defied convention by running away to live together.

Extraordinary Female Affection was the title of a 1790 newspaper article on two female friends, Miss Sarah Ponsonby and Lady Eleanor Butler, who had defied convention by running away to live together.

The article, which appeared in St. James’s Chronicle, the General Evening Post and the London Chronicle, made it quite plain what the author thought of such goings-on, describing Butler in disapproving tones as of masculine appearance (this was true) and the couple as bear[ing] a strange antipathy to the male sex, whom they take every opportunity of avoiding – which was decidedly false; the ladies entertained many male guests, including the Duke of Wellington, Sir Walter Scott and William Wordsworth. The author described Ponsonby as Butler’s particular friend and, more censoriously (for the time), the bar to all matrimonial union. Needless to say, the ladies were less than happy with the tone of the article, and took legal advice.

However, the attitude of society in general was very different. The zeitgeist of the time was for romanticising all things, including nature, landscapes and the bonds of friendship, and their story captured the popular (educated) imagination. The ladies were celebrated for their romantic friendship and presumed celibacy, to the extent that they became celebrities of the day—similarly, one supposes, to many early female Christian martyrs who were lauded for their chastity as much as for any miraculous deeds.

There is plenty of the romantic in the ladies’ story: both were from aristocratic (though attainted) families in Ireland and both were under intolerable pressure from their families—Butler to enter a convent, and Ponsonby to accept the advances of her guardian. Close friends for many years, when Ponsonby was 23 and Butler, 39, they hatched a plot to run away together dressed as men, taking with them a pet dog and a pistol. Having ridden through the night to catch a ferry to Wales, they were hit by what we tend to think of as a bane of modern life: transport cancellation. Unluckily, they were discovered and brought back home.

Much as for Marianne in Sense and Sensibility by Jane Austen (who would have known of the Ladies of Llangollen), for Ponsonby, romantic disappointment was swiftly followed by dangerous illness. To comfort her friend—and escape her family, who had stepped up attempts to ship her off to that convent—Butler fled to Ponsonby’s house, where she concealed herself in her friend’s bedroom, aided by a sympathetic maid, Mary Carryl. When, after some days, she was discovered, the families evidently decided that enough was enough, threw up their hands and consented to the couple removing to Wales as they’d wanted all along.

Ponsonby later wrote up the tale in Account of a Journey in Wales perform’d in May 1778 by Two Fugitive Ladies, showing she had an eye for a catchy, if long-winded, title.

The ladies eventually found a house near Llangollen where they settled down and lived happily for the next fifty years in quiet retirement—apart from the steady stream of society visitors.

Were they lovers? Nobody knows. Even in their own lifetimes, opinion was divided. They addressed each other in terms used between husband and wife, and they shared a bed—but this was not unusual behaviour for friends at the time. They also cropped their hair and wore masculine hats and coats—although retaining their petticoats. Their visitors included Anne Lister, who was, by her own writings, what we would nowadays term a lesbian and had physical affairs with women, and Anna Seward, who although romantically interested in women is not known to have had a sexual relationship with any.

It’s often speculated that Butler, the more obviously masculine of the two, was a lesbian, but that Ponsonby, the younger, more femme partner, might have been just as happy with a man. I personally tend to take this more as evidence for the enduring quality of stereotypes than as anything else.

Further reading: Rictor Norton (Ed.), “Extraordinary Female Affection, 1790”, Homosexuality in Eighteenth-Century England: A Sourcebook, 22 April 2005, updated 15 June 2005 <http://rictornorton.co.uk/eighteen/1790extr.htm>.

Nancy Meyer, Regency Researcher http://www.regencyresearcher.com/pages/ladies.html

***

JL Merrow is that rare beast, an English person who refuses to drink tea. She read Natural Sciences at Cambridge, where she learned many things, chief amongst which was that she never wanted to see the inside of a lab ever again. Her one regret is that she never mastered the ability of punting one-handed whilst holding a glass of champagne.

JL Merrow is that rare beast, an English person who refuses to drink tea. She read Natural Sciences at Cambridge, where she learned many things, chief amongst which was that she never wanted to see the inside of a lab ever again. Her one regret is that she never mastered the ability of punting one-handed whilst holding a glass of champagne.

JL Merrow is a member of the Romantic Novelists’ Association, International Thriller Writers, Verulam Writers’ Circle and the UK GLBTQ Fiction Meet organising team.

Find JL Merrow online at: www.jlmerrow.com, on Twitter as @jlmerrow, and on Facebook at http://www.facebook.com/jl.merrow

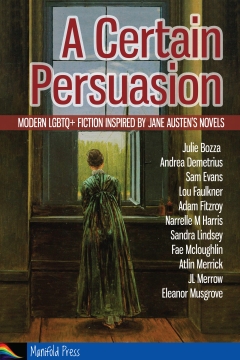

JL Merrow is the author of “A Particular Friend” which appears in A Certain Persuasion, a new anthology of stories set in and around the writings of Jane Austen, featuring LGBTQIA characters, which was released on 1st November.

JL Merrow is the author of “A Particular Friend” which appears in A Certain Persuasion, a new anthology of stories set in and around the writings of Jane Austen, featuring LGBTQIA characters, which was released on 1st November.

Thirteen stories from eleven authors, exploring the world of Jane Austen and celebrating her influence on ours.

Being cousins-by-marriage doesn’t deter William Elliot from pursuing Richard Musgrove in Lyme; nor does it prevent Elinor Dashwood falling in love with Ada Ferrars. Surprises are in store for Emma Woodhouse while visiting Harriet Smith; for William Price mentoring a seaman on board the Thrush; and for Adam Otelian befriending his children’s governess, Miss Hay. Margaret Dashwood seeks an alternative to the happy marriages chosen by her sisters; and Susan Price ponders just such a possibility with Mrs Lynd. One Fitzwilliam Darcy is plagued by constant reports of convictions for ‘unnatural’ crimes; while another must work out how to secure the Pemberley inheritance for her family.

Meanwhile, a modern-day Darcy meets the enigmatic Lint on the edge of Pemberley Cliff; while another struggles to live up to wearing Colin Firth’s breeches on a celebrity dance show. Cooper is confronted by his lost love at a book club meeting in Melbourne while reading Persuasion; and Ashley finds more than he’d bargained for at the Jane Austen museum in Bath.

Smashwords| Amazon | ARe