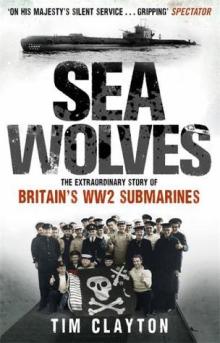

I’ve just finished reading Sea Wolves by Tim Clayton with a view to rewriting my WWII submarine story ‘Under the Radar’ for possible submission.

I’ve just finished reading Sea Wolves by Tim Clayton with a view to rewriting my WWII submarine story ‘Under the Radar’ for possible submission.

This book had the capacity to have me in tears–the sheer loss of human life in the submarine service was staggering–but it didn’t. And it wasn’t that the book didn’t focus on the human face of the service. There were human stories mixed in with the development of the submarine and the progression of the war and how the Powers That Be viewed the use of submarines in the war effort. Tales of their life at play as well as time spent on duty, of falling in love, and, in most cases, of how they died.

The origins of the submarine service, and, to a degree, the chapters on the pre-war service were fine as background information to the main event. The problem for me, and I think the reason that I didn’t connect with the book on an emotional level, was that once war was declared the author chose to focus on the different areas and campaigns. Chapters on the invasion of Norway, the submarine base at Malta, Japan taking over the Pacific, the development of midget subs.

The same names cropped up again and again as they moved from one submarine to another or were promoted—quickly, ensuring relatively young officers in a service that many didn’t want to volunteer for—and transferred to another campaign. I’d say eighty to ninety percent of the names mentioned died or were on board a sub that ended up being missing in action. And yet I could not cry for them. I recognised the names, recalled other submarines they had served on, people they had served with, even on occasions the women they had courted or married. And yet I could not cry for them. I felt the despair of such vast losses, the futility of some of the campaigns (midget subs may have well have been titled suicide missions), their realisation of time running out, could often tell which report would be each participants last. And yet I could not cry for them.

I can’t deny that I cry easily. So why couldn’t I cry here?

Because the author would not let me. There was no continuity to each participant’s story. The information was probably all there, but in most cases it was spread over so many chapters that it left me feeling disconnected from the human aspect of their tale, and ultimately their death. The characters in this book—and believe me there were many interesting characters in the submarine service—were nothing but pawns in a document that detailed the campaigns and what happened to damn near every ship. In the end, despite the final chapter and his acknowledgements, I felt that the author treated the personnel of the submarine service no better than the Powers That Be, as a means to an end.

As a documentation of the development of submarines, of how it felt to be on board in wartime, and the changing view of the PTB this book could not be faulted. If you want to know what happened to most subs in the service, again this book is probably for you.

However as a celebration of the characters and mavericks that made up this service, as a thank you to them for putting their life on the line every time they stepped on board (even in peace time or friendly waters) this book was sorely lacking.

If you want to check out Sea Wolves or see what other folks thought of it, here’s the link on Goodreads.