History is littered with people whose lives and achievements would risk being unbelievable in historical fiction. One famous example is Adrian Carton de Wiart, who fought in the Boer War and both World Wars. As it says in the introductory paragraph to his Wikipedia entry:

He served in the Boer War, First World War, and Second World War; was shot in the face, head, stomach, ankle, leg, hip, and ear; survived two plane crashes; tunnelled out of a prisoner-of-war camp; and tore off his own fingers when a doctor refused to amputate them. Describing his experiences in the First World War, he wrote, “Frankly I had enjoyed the war.”

(If you want an alternative source to Wikipedia, here’s a BBC article about him)

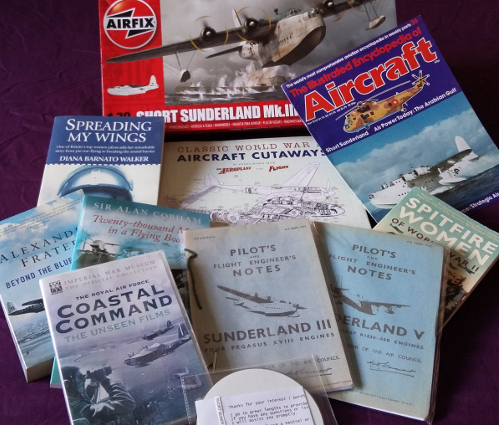

In the course of researching Under Leaden Skies, I came across accounts of a number of people and events which made my jaw drop, and I’d like to share a few of them here.

Stewart Keith-Jopp

Keith-Jopp was one of three one-armed pilots who served in the Air Transport Auxilliary, having lost an arm – reportedly on a bombing run – as well as an eye during World War 1. He certainly seemed to have been quite an influence in the ATA, and was the man I had in mind that my character, Drummond, had met, when he mentions to Teddy that “I know for sure there’s at least one chap flies for them who’s only got one arm.”

There’s a little more information about Stewart Keith-Jopp on the RAF Museum website, but I didn’t find any further details about the other two one-armed pilots, First Officer R.A Corrie, and the Honourable Charles Dutton (later Lord Sherborne), other than their mention in Spitfire Women.

Douglas Fairweather

Despite (or perhaps because of) his name, Captain Fairweather was renowned in the ATA for his ability to fly, and arrive safely at his destination, in the most atrocious of weather. The best account I found of his method is in Diana Barnato Walker’s Spreading My Wings, as her style of writing really suits this gentleman’s apparent approach to life.

ATA pilots were supposed to carry a map to aid navigation: Fairweather carried with him a 2″x3″ map of the British Isles “quite obviously torn from nothing larger than the back of a pocket diary”, and according to Spitfire Women, at one point the map he carried was of Roman Britain! His method of navigation in poor or nil visibility required knowing the direction and distance of his destination from where he had taken off, and flying at a steady speed. Once airborne, he chain-smoked cigarettes. He knew that each cigarette lasted him 7 minutes, and by lighting each cigarette from the previous one, he timed his flight and therefore knew exactly how far he’d flown!

Smoking was, as we would these days expect, forbidden. So on landing he brushed the ash from his uniform and made sure to open the cockpit window in time for the smoke and smell to dissipate.

Veronica Volkersz, the first British woman to fly a jet

Whilst the above examples are of people whose story might be seen to stretch the boundaries of believability in fiction, in Volkersz’s case it is the circumstances around her first jet-powered flight which stretch modern credulity. In an earlier draft of Under Leaden Skies, I based Teddy’s first jet-flight quite closely on Volkersz’s, but the feedback I received was along the lines of “Surely he had some extra training first? They wouldn’t just put people in jets with no training?”

Erm… sorry to tell you folks, but that is exactly what they did! Verging on incredulous for us, used to the dangers of jet engines, and well aware of the differences between jet-propelled craft and propeller-driven ones. As stated in Giles Whittell’s Spitfire Women (which, as you’ve probably gathered from the number of times I’ve mentioned it, is an excellent book & you should read it if you haven’t already):

[Volkersz] was offered no conversion course, no cockpit inspection, no helpful hints, no comment. Just a new four by five inch card to be inserted in her ringbound Ferry Pilot’s Notes in alphabetical order between Martinet and Oxford, to be glanced at on her way out to dispersal.

Of course, she was a brilliant pilot, and had requested a chance to fly a Meteor. No doubt also, that all pilots would have kept abreast of developments as much as they could – the aviation magazines Flight and The Aeroplane were published throughout the war, and of course pilots would talk to each other, so I am sure that Volkersz’s commanding officer would have been assured of her ability to adapt to and handle the differences.

However, I will admit that the “two-hour lecture” and extra time in the schedule for Teddy to familiarise himself with the Meteor which appear in my story are entirely fictional… There’s only so far you can push the suspension of disbelief, after all 😉